Protestantism: Lights and Shadows

Lights of Protestantism: Quotes

from the Popes

Pope Francis:

With

gratitude we acknowledge that the Reformation helped give greater centrality to

sacred Scripture in the Church’s life. Through shared hearing of the word of

God in the Scriptures, important steps forward have been taken in the dialogue

between the Catholic Church and the Lutheran World Federation, whose fiftieth

anniversary we are presently celebrating. Let us ask the Lord that his word may

keep us united, for it is a source of nourishment and life; without its

inspiration we can do nothing.

The spiritual experience of Martin Luther challenges us to

remember that apart from God we can do nothing. “How can I get a propitious

God?” This is the question that haunted Luther. In effect, the question of a

just relationship with God is the decisive question for our lives. As we know,

Luther encountered that propitious God in the Good News of Jesus, incarnate,

dead and risen. With the concept “by grace alone”, he reminds us

that God always takes the initiative, prior to any human response, even as he

seeks to awaken that response. The doctrine of justification thus expresses the

essence of human existence before God.

Pope Benedict XVI:

As the

Bishop of Rome, it is deeply moving for me to be meeting you here in the ancient

Augustinian convent in Erfurt. As we have just heard, this is where Luther

studied theology.

What constantly exercised him was the question of God, the deep passion and

driving force of his whole life’s journey. “How do I receive the grace of

God?”: this question struck him in the heart and lay at the foundation of all

his theological searching and inner struggle. For Luther theology was no mere

academic pursuit, but the struggle for oneself, which in turn was a struggle for

and with God.

“How do I receive the grace of God?” The fact that this question

was the driving force of his whole life never ceases to make a deep impression

on me.

The question: what is God’s position towards me,

where do I stand before God? – Luther’s burning question must once more,

doubtless in a new form, become our question too, not an academic question, but

a real one. In my view, this is the first summons we should attend to in our

encounter with Martin Luther.

Another important point: God, the one God, creator of heaven and

earth, is no mere philosophical hypothesis regarding the origins of the

universe. This God has a face, and he has spoken to us. He became one of us in

the man Jesus Christ – who is both true God and true man. Luther’s thinking,

his whole spirituality, was thoroughly Christocentric: “What promotes Christ’s

cause” was for Luther the decisive hermeneutical criterion for the exegesis of

sacred Scripture. This presupposes, however, that Christ is at the heart of our

spirituality and that love for him, living in communion with him, is what

guides our life.

=======================

Protestantism's Shadows. My article at Wikipedia.

| Part of a series on |

| Protestantism |

|---|

|

Criticism of Protestantism covers critiques and questions raised about Protestantism, the movement based on Martin Luther's Reformation principles of 1517. Criticisms come mainly from Catholic and Orthodox sources, although Protestant denominations have also engaged in self-critique and criticized one another.[2]

The biblical critique, according to Bible-based Protestants who converted to Catholicism, asserts that the doctrines of principal branches of Protestantism, even in their foundational principles, are unbiblical and unfaithful to the practices and beliefs of the Church of the Bible. Sola scriptura of the Lutheran and Reformedbranches[3] and prima scriptura of the Anglican Communion and the Methodist Churches are "self-refuting", according to critics, because the Bible as to its canon and nature was determined by Catholic synods, presupposes the Church and its tradition, never mentions the exclusivity and primacy of the authority of Scripture nor the canon of Scripture, and teaches that "the Church", not the Bible, "is the pillar and the bulwark of the truth". (1 Tim 3:15) Also, sola scriptura is contradicted by the Bible teaching about other sources of revealed truth such as tradition, spoken word, and a Council. According to the critics, sola fide, another concept originated by Lutheran and Reformed theologians, is directly contradicted by the Biblical teaching such as "a man is justified by works not by faith alone" (James 2:24). Critics also challenge the historicity of the Great Apostasy, a premise of the Reformation, given the "total silence" in the historical accounts, and its biblical foundation given Jesus' promises of continual divine presence in his Church which the Bible refers to as his body, inseparable from him, and the historically verified existence of unbroken apostolic succession based on the biblical principle of "his office (episkopen) let another take." (Ps 108:8; Acts1:20)

The historical, sociological and ecclesiological critique points to the disparity of Protestantism with early Christian practices and the teachings of the Church Fathers, the 16th century foundation of Protestantism, the problematic moral quality of its founders, and its fragmentation and doctrinal contradictions that foster schism and disunity in contrast to the unity of the Church described in the New Testament as being "united in the same mind and same judgement". (1 Cor 1:10) This fragmentation means, according to critics, that each autonomous Protestant denomination, with its unique truth claims, have limited numbers concentrated in one geographical area vis-a-vis world population, a situation at variance with the universal scope of Christ's one Church. A few critics, supported by leading modern scholars, also say that Protestants brought about the creation of the black legend or false propaganda against Catholics, in contravention of the commandment of "not bearing false witness."[4] Critics also assert that the infidelity of most Protestant groups to the unanimous Christian teaching against contraception up to 1930 led to the decadent sexual revolution with its pleasure-seeking non-procreative sex. Historian Brad Stephan Gregory in a multi-awarded book published by Harvard University Press traced today's hyperplural, relativistic, morally subjectivistic, permissive, individualistic, consumerist, state-controlled, morality and religion free, secularized society to the Reformation's giving sole authority to the bible that can be individually interpreted, its state-controlled churches, faith-alone salvation without need for human cooperation, and Protestantism's divergent moral teachings.

Contents

[hide]Sources of criticism[edit]

While the Catholic leaders have been seeing the positive side of the founder of Protestantism, Martin Luther, calling him "thoroughly Christocentric"[5] and saying that his intention was "to renew the Church and not to divide it",[6] Catholic doctrine views Protestantism as "suffering from defects", not possessing the fullness of truth[7] and lacking "the fullness of the means of salvation".[8] A number of Protestant converts to Catholicism through the centuries have written their criticism of Protestantism in explaining their conversion.

Orthodox Christians also criticize Protestantism in its lack of a visible church,[9] and in its adherence to some of the aspects of Western Christianity including Roman Catholicism.[10]

Protestants also engage in self-criticism, a special target of which is the fragmentation of Protestant denominations.[2] In addition, due to the fact that Protestantism is not a monolithic faith tradition, some Protestant denominations criticize the beliefs of other Protestant denominations. For example, the Reformed Churches criticize the Methodist Churches for the latter denomination's belief in the doctrine of unlimited atonement,[11] in a long-term debate between Calvinists and Arminians.

Biblical critique[edit]

Starting around the 1990s, a series of key conversions from Protestantism to Catholicism were based on arguments that Protestantism is unbiblical. This movement was led, among others, by Presbyterian biblical scholar Scott Hahn and his wife Kimberly, whose conversion story is told in Rome Sweet Home and later in audio form called The Tape, as it is considered as "the most widely distributed Catholic audiotape of all time".[12][13] Other conversion stories critical of Protestantism were told in the two volumes of Surprised by Truth, and a substantial number of biblical argumentation is found in websites, including biblicalcatholic.com,[14] scripturecatholic.com,[15] and protestanterrors.com.[16]

While Protestantism is praised by Pope Francis as Bible-centered and Protestantism accepts the Bible as sole or first authority,[17] being "God-breathed and useful for teaching and correcting in righteousness" (1 Tim 3:16), it deliberately disregards specific Biblical passages and does not take them literally as God's word, according to critics. As explained by John Salsa, among the foremost reasons why ex-Protestants find Protestantism unbiblical, and Catholicism biblical are: (1) Authority: the giving of the keys of the Kingdom to Peter in Matthew 16:18-19; (2) Church, and not the bible, as "the pillar and bulwark of the truth" in 1 Timothy 3:15; (3) Tradition: the command of Paul to "hold to the traditions which you were taught by us, either by word of mouth or by letter" in 2 Thessalonians 2:15; (4) "Baptism now saves you", in 1 Peter 3:21 vs faith alone; (5) Confession: "If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven" in John 20:23; (6) Eucharist:"my flesh is food indeed" and "Will you also go away?" in John 6:53-58, 66-67; (7) Eucharist: "Whoever eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of profaning the body and blood of the Lord" in 1 Corinthians 11:27 to show that Jesus was not speaking symbolically; (8) Anointing of the sick with forgiveness of sins in James 5:14-15; (9) Suffering: "I complete what is lacking in Christ's affliction in Colossians 1:24; (10) Justification not by faith alone:"a man is justified by works and not by faith alone" in James 2:24.[18][19]

Criticism of foundational principles[edit]

Sola scriptura[edit]

Sola scriptura, originated by the Lutheran Churches and Reformed Churches during the Reformation,[3] is a formal principle of many key Protestant Christian denominations. Baptist Churches state that sola scriptura is self-authenticating and sufficient of itself to be the final authority of Christian doctrine.

In contrast, the Anglican Communion and the Methodist Church uphold the doctrine of prima scriptura, which holds that Sacred Tradition, Reason and Experience are sources of Christian dogma, but are subordinate to Sacred Scripture, which is the primary authority.[20][21]

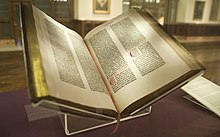

Bible as Catholic book[edit]

Luther himself said that "We are compelled to concede to the Papists that they have the Word of God, that we have received It from them, and that without them we should have no knowledge of It at all."[22] "A council probably held at Rome in 382 under St. Damasus", states The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, "gave a complete list of the canonical books of both the Old Testament and the New Testament".[23]

Former Protestant Jimmy Akin asserted that the "Bible-only" position was self-refuting as the Bible itself does not prescribe the official list or canon of the Bible books, and he had to trust the Catholic church and its claim to infallibility in its choice of books. Since there was a debate in the early Church on the authorship and canonical status of a number of New Testament books (e.g., Hebrews, Revelation, James, 2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, and Jude) and the Church decided which belonged to the canon, this meant that the Protestant foundational doctrine on the very nature of Scripture was dependent on the Church. Thus, if the Bible is infallible, then the Church must be infallible and can do other infallible actions, a doctrine that Protestants deny.[24] Peter Kreeft explains that "a cause [in this case, the Church] can never be less than its effect [the Bible].... If the Church has no divine inspiration and no infallibility, no divine authority, then neither can the New Testament".[25] He offered a synthesis by stating, "the Protestant Reformation began when a Catholic monk rediscovered a Catholic doctrine in a Catholic book."[26]

Bible, church and tradition[edit]

Critics argue that New Testament books were written during a period that starts two decades after the death of Jesus Christ, and thus the Church precedes the Bible, and "the Bible presupposes the Church". The New Testament is not a building manual per se but a description of a community with established policies and practices of devotion, structures of authority and decision-making, says Scott Hahn.[27] Jesus did not write anything nor command his disciples to write, but "to do this" in reference to the Eucharist. The above also implies that the early Christians did not have a Bible for their salvation, and that it was through the aid of oral tradition that the present Bible was written. Both Catholic and Protestant theologians explain the importance and reliability of oral tradition as the basis of the Bible, since oral tradition was a self-correcting effort of an entire community adept at memorization, striving to faithfully keep the most important event and truths that it knows,[28] supported by the Holy Spirit who "leads to all truth". St. Paul spoke about a series of faithful passing on of teaching, telling Timothy about entrusting the spoken truths he himself received to faithful men who in turn will teach them: "[W]hat you have heard from me before many witnesses entrust to faithful men who will be able to teach others also" (2 Tim. 2:2).

Critics also argue that the Bible itself emphasizes that Christians should faithfully adhere to oral tradition that comes from the Apostles, and not just to scripture. St. Paul teaches: Stand firm and hold to the traditions (paradosis) which you were taught by us, either by word of mouth (dia logos) or by letter. (2 Thessalonians 2:15; italics added)

Unbiblical doctrine[edit]

According to Dave Armstrong, a former nondenominational Christian, "no biblical passage teaches that Scripture is the formal authority or rule of faith in isolation from the Church and Tradition. Sola scriptura can't even be deduced from implicit passages."[29] The relevance of Timothy 3:16 regarding all scripture being inspired and profitable is criticized since it does not categorically state that scripture is the only one with these qualities and does not preclude others from having these qualities.[30]

Armstrong lists nine other "refutations" to Sola Scriptura such as "The Word of God refers to oral teaching also", quoting St. Paul's saying "the word of God which you heard from us", (1 Thessalonians 2:2-13), the apostles exercised authority at the Council of Jerusalem, "Paul casually assumes that his passed-down tradition Is infallible and binding", referring to St. Paul's words "avoid those in opposition to the doctrine which you have been taught" (Rom. 16:17), and Sola Scriptura is a fallacious circular reasoning, the conclusion is the same as the premise.

Protestant traditional defense states that the Bible is "a fallible collection of infallible documents".[13] Critics say that this leaves the Christian readers uncertain on whether they are reading a falsehood or the truth.[13] Thus they refer to Biblical evidence wherein "God's authoritative Word is to be found in the Church: her Tradition (2 Th 2:15; 3:6) as well as her preaching and teaching (1 Pet 1:25; 2 Pet 1:20-21; Mt 18:17)," and that there needs to be thinking and authorized interpreter, given that the Bible itself warned "that it contains difficult and confusing information which is capable of (if not prone to) being twisted into all sorts of fanciful and false interpretations (2 Peter 3:16)".[31]

Critics of Protestantism argue that since God wanted all men to be saved and come to the knowledge of the truth, he set up authorities to provide authoritative interpretation that would prevent false interpretations that can mislead his flock. They refer to the passage that give Peter the keys of the kingdom, which according to Scott Hahn, is understood by the Jews who heard Jesus' conferral as the powers of the primer minister of the King and chief teacher of the kingdom, based on the text of Isaiah 22 where the king grants full authority to a chief steward.[32][33]

Moreover, some ex-Protestants have expressed their anxiety over the salvation and Christianization of millions of illiterate people in the world, who are unable to draw from scriptures.[34] The Bible itself says "faith comes from hearing". (Rom 10:17)

Justification by faith alone and grace alone[edit]

Sola fide as unbiblical[edit]

At "the crux of the disputes" is the doctrine on justification[35] and sola fide is the principle on which Protestantism "stands or falls", as per Luther.

Contrary to some Protestant perception, the immediate official Catholic response to the Reformation, the Council of Trent, affirmed in 1547 a doctrine that is part of its tradition,[36] as regards the importance of faith: "we are therefore considered to be justified by faith, because faith is the beginning of human salvation, the foundation, and the root of all Justification...none of those things which precede justification --whether faith or works-- merit the grace itself of justification."[37] Thus, in 1999 the Catholic Church and the Lutherans (later joined by the Methodists) have issued Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification, showing "a common understanding" of justification: "By grace alone, in faith in Christ's saving work and not because of any merit on our part, we are accepted by God and receive the Holy Spirit, who renews our hearts while equipping and calling us to good works."

Although an important step forward in the work of ecumenism, the declaration continues to show the differences of thought. Lutherans continue to uphold Luther'a doctrine that "human beings are incapable of cooperating in their salvation.... God justifies sinners in faith alone (sola fide)."[38] On the other hand, the Methodist Churches have always emphasized that ordinarily, both faith and good works play a role in salvation; in particular, the works of piety and the works of mercy, in Wesleyan-Arminian theology, are "indispensible for our sanctification".[39]Bishop Scott J. Jones in United Methodist Doctrine says that faith is necessary to salvation unconditionally, since the good thief was saved even though he didn't have time to do any good works. Good works are necessary only conditionally, that is if there is time and opportunity, which is true for the vast majority.

Some Protestants are criticized for using the salvation of the good thief as a proof of sola fide, when the good thief performed good works by rebuking the other thief for mocking Jesus, admitting that "we are condemned justly", and affirming the truth of Jesus, "this man has done nothing wrong".[40][41]

Critics argue that (1) sola fide (only faith and no other factor saves) does not appear in the Bible, (2) the only time the phrase appears in the Bible, it is expressly denied: "a man is justified by works and not by faith alone," (James 2:24), (3) Luther inserted the word "alone" in his German translation, although the word was not in the Greek original, (4) Paul does teach salvation by faith without implying the exclusivity of "only", but in other parts he stresses, "the only thing that counts is faith working, or expressing itself, (energeo) through love." (Gal 5:6)[42][43]

Scripture Catholic, moreover, gives dozens of scriptural passages to prove each one of these statements: (1) faith justifies initially, but works perfect and complete justification, (2) modern scholarship has established that Rom 3:28, which Protestants use to de-emphasize works, is interpreted to mean that "a man is justified by faith apart from works of the Torah", i.e. these works of the law refer to the ceremonial rites peculiar to Judaism, (3) justification is an inner change of the person (an infusion of grace). It is not just a declaration by God (an external imputation), (4) Justification is ongoing (not a one-time event); (4) Jesus and Apostles teach that works are necessary for justification.[44]

Critics argue that the Protestant faith declaration of "accepting Christ as savior" is not found in the Bible. They also state that the Bible teaches that "baptism now saves you" (1 Peter 3:20-21)[45] and that "being born again" is interpreted by the following verse about "being baptized by water and the Spirit".

Human cooperation with divine grace[edit]

Bishop Robert Barron said that "The single most significant contribution of Martin Luther and those who followed in his theological path was the stress on the primacy of grace", protesting against "Pelagianism, or the illusion of auto-salvation".

But contrary to some Protestant thinking, according to former Baptist minister Deal Hudson, "The constant teaching of the Catholic Church throughout the ages has been that salvation is bestowed alone by God's grace. This was not the singular discovery of the Reformation."[46][47] The Council of Trent taught that "the beginning of Justification is to be derived from the prevenient grace of God, through Jesus Christ." And so Benedict XVI said in 2006, that "it is to God and his grace alone that we owe what we are as Christians."[48]

Still, Catholic doctrine counters the Protestant teaching that "human beings are incapable of cooperating in their salvation". As the Catholic Catechism states: "The divine initiative in the work of grace precedes, prepares, and elicits the free response of man. Grace responds to the deepest yearnings of human freedom, calls freedom to cooperate with it, and perfects freedom." Thus, Bishop Barron said that "because of the unique manner in which God relates to creation, this human cooperation doesn’t compromise the absolute primacy of the divine love", as he said is shown in Isaiah 26:12: "Lord, you establish peace for us; all that we have accomplished you have done for us."[49]

Louis Bouyer, author of the Spirit of Protestantism, further points to other scriptural passages: "grace, for St. Paul, however freely given, involves what he calls 'the new creation', the appearance in us of a 'new man'.... So far from suppressing the efforts of man, ... he himself tells us to 'work out your salvation with fear and trembling', at the very moment when he affirms that '... knowing that it is God who works in you both to will and to accomplish.'... all is grace in our salvation, but at the same time grace is not opposed to human acts and endeavor in order to attain salvation, but arouses them and exacts their performance."[50]

Justified: cleansed from sin, alive in Christ[edit]

The Vatican's note in response to the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification said that the Protestant formula "at the same time righteous and sinner" ... is not acceptable: "In baptism everything that is really sin is taken away, and so, in those who are born anew there is nothing that is hateful to God. It follows that the concupiscence [disordered desire] that remains in the baptised is not, properly speaking, sin."[51]

The Catechism of the Catholic Church's article on Justification quotes the letter to the Romans in its explanation:

- The grace of the Holy Spirit has the power to justify us, that is, to cleanse us from our sins and to communicate to us "the righteousness of God through faith in Jesus Christ" and through Baptism. (Rom 3:22. Cf. 6:3-4.) But if we have died with Christ, we believe that we shall also live with him.... So you also must consider yourselves as dead to sin and alive to God in Christ Jesus.( Rom 6:8-11)

Justification, New Covenant and Sonship[edit]

Scott Hahn also says that Protestantism misses the deepest biblical meaning of justification in the New Covenant, since Jesus didn't just save us from sin, but also save us for divine sonship. Covenant in the Bible means a sacred kinship bond that brought people into a family relationship, and the new covenant established by Jesus Christ is an establishment of a worldwide family. Jesus and the apostles, Hahn says, used family-based language to describe his work of salvation: God is Father, Christ is Son and the firstborn among brethren, heaven as a marriage feast, the Church is the spouse of God, Christians as children of God. The Pope as Papa and Holy Father, and Mary as Mother of Christians, are an essential part of God's family which is the Church.

Great apostasy[edit]

A foundational premise for the need of the Protestant doctrines of the solas, such as sola scriptura and sola fide, is the doctrine that traditional Christianity especially the Catholic church has fallen away from the primitive principles of Christianity, a doctrine known as the Great apostasy.

Non-historical and unbiblical[edit]

Historically, say critics, "There is no mention in any of [Church Fathers'] writings of a great apostasy or any sort of battle for the faith on such a scale.... Even if it is assumed that the Church Fathers were part of the apostasy it is likely that they would have mentioned it – even if just to condemn the "true" Christians! But there is no sign in the writings of the Church Fathers of this heresy, nor are there any other writings which support the notion. History is totally silent."[52] Also, the meeting of Christianity with Greek culture is not apostasy but intrinsic to Christianity given that the Bible narrates the vision calling Paul to Macedonia, and the fact that the New Testament itself, source of Christian revelation, was written in Greek, a pagan language, and written in today's Bibles in Latin script.[53][54] Rod Bennet in The Apostasy that Wasn't gathered historical evidence and disproved his own previous belief as Baptist and Evangelical in the Great Apostasy, and concluded that it is popular but fiction. He narrated most especially the work of St. Athanasius of Alexandria who was later given the title of "Father of Orthodoxy" in stopping the heresy of Arianism despite the intrigue of the rulers of the Empire and their military might.[55] Moreover, the argument that the excesses and misconduct of the papacy constitute apostasy is misplaced, according to critics, since Jesus' conduct towards Peter shows a clear distinction between the misconduct of Peter (denial and "Get behind me Satan") and affirmation of Peter's office to govern and teach ("feed my sheep" after the denial, and "keys of the kingdom").[56][57]

Catholic converts from Protestantism have been criticizing the Great Apostasy as unscriptural on the basis of Jesus' promise to his apostles "I will be with you until the end of the age," and "that the Paraclete will lead you all the truth", plus his promise to Peter "On this rock I will build my church, and the gates of Hell shall not prevail against it." Also, the Church is the body of Christ (1 Cor 12:27), and he is inseparable from his body. Jesus himself told St. Paul when he was persecuting the Church, that he was "persecuting me", (Acts 9:4-5) thus identifies himself with his Church as he once said that "I am the vine, you are the branches." (Jn 15:5) They also assert that it is the Church, and not the scriptures, that is the "pillar and bulwark of the truth". (1 Tim 3:15) "It's inconceivable that [Jesus]", says Patrick Madrid, "would permit his body to disintegrate under the attacks of Satan. The apostle John reminds us that Jesus is greater than Satan. (1 John 4:4)."[58]

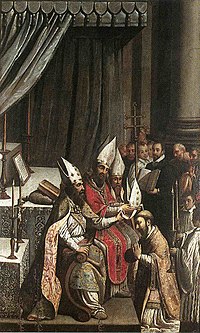

Apostolic succession and ordained authority[edit]

Aside from a disregard to the promises of Jesus to his Church that makes him unreliable when he gives his word, critics state that Protestant acceptance of the Great Apostasy implies their non-acceptance of the biblical teaching on apostolic succession in the Catholic Church and in the Orthodox Churches, a doctrine that the Apostles appointed successors to their authoritative office of governing and preserving the truth in the Church throughout the centuries. At the same time, a number of Protestant Churches, including many Lutheran Churches, the Moravian Church, and the Anglican Communion teach that they ordain their clergy in lines of apostolic succession,[59] and the Eastern Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, in 1922, recognised Anglican orders as valid.[60][61]

The Roman Catholic Church has rejected the validity of Anglican apostolic succession as well as that of other Protestant Churches,[62] saying as regards the latter that "the proclamation of sola scriptura led inevitably to an obscuring of the older idea of the Church and its priesthood. Thus through the centuries, the imposition of hands either by men already ordained or by others was often in practice abandoned. Where it did take place, it did not have the same meaning as in the Church of Tradition."[63]

As to the biblical basis of unbroken apostolic succession, Scott Hahn refers to the principle behind the Church decision to ordain a successor to Judas as the twelfth apostle, quoting Ps 108:8 "His office let another take". He explains that original Greek word for office is episkopen, from which is derived the word bishop, leading the Protestant King James Version to translate this as "his bishopric let another take".

Scripture Catholic argues there are dozens of scriptural passages that show that "Ordained Leaders Share in Jesus' Ministry and Authority" (e.g. "he who receives you, receives Me, and he who rejects you"), "Authority is Transferred by the Sacrament of Ordination" (e.g. laying of the hands, the gift of authority), "Jesus Wants Us to Obey Apostolic Authority".[64]

Critics say that non-acceptance of the doctrine of apostolic succession is not only unbiblical but also does not correspond to the practices of the early Church and its knowledge of the mind of Christ. They point to the Letter of St. Clement of Rome dated 98 A.D.: "Our Apostles knew through our Lord Jesus Christ that there would be dissension over the bishop's office. That is why, having received complete foreknowledge, they appointed the aforesaid persons, and afterwards they provided a continuance, that if these should fall asleep, other approved men should succeed them."

St. Irenaeus' words in 189 A.D. "we are in a position to enumerate those who were instituted bishops by the apostles and their successors down to our own times," are used by critics to refer to documentary evidence regarding a continuous, unbroken chain of succession in the Catholic Church that was abandoned through the Reformation.[65]

Criticism of other doctrines[edit]

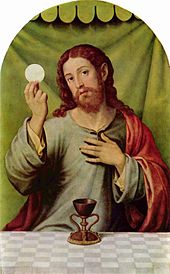

Eucharist[edit]

According to the doctrine of Roman Catholic Church, those Protestant denominations that have abandoned the Church's continuous apostolic succession, have lost not just the sanctifying powers of legitimately ordained priests to celebrate the sacraments, but also what is most important in Christianity that can only come from these priests: the real presence, or fullness of presence, of Jesus in the Eucharist, which Catholics say contains "the whole spiritual good of the Church, namely Christ himself", and makes the Church into one body. (cf. 1 Cor 10:16-17: we who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one bread)[66] Thus, say critics, Protestants have departed from "the witness of the whole of the Christian Church for 1,600 years",[67] and, because of that, as Peter Kreeft says, they miss the closest and sweetest possible union with Jesus Christ here on earth.[68]

Because of the above and because they have failed to take Jesus' words in the Bible literally as regards the Eucharist, critics say Protestant Churches[69] including the Anglican, Lutheran, Methodist, and Reformed traditions (as well as Orthodox Churches), each teach a different form of the doctrine of the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist,[70][71] with Lutherans affirming Christ's presence as a sacramental union and Reformed/Presbyterian Christians affirming a pneumatic presence.[71][72] Anabaptist, Plymouth Brethren and some independent churches teach that the Eucharist is memorial,[73] and do not hold to a belief in the real presence of Jesus in the Eucharist.

Jesus said when he instituted the Eucharist "This is my body.... This is the blood of New Covenant,"and that "he who eats my flesh has eternal life". Critics say that this is no figure of speech or mere symbol, for Jesus' use of graphic words shocked his listeners as the original Greek words say "chew" and "gnaw" his flesh[13][27]. Also Jesus did not give in when "many of his disciples" left due to this "hard saying" (Jn 6:48-68), and St. Paul taught that he who eats the bread unworthily is "guilty of profaning the Lord's body" (1 Cor 11:28). The early Christians Fathers such as St. Ignatius of Antioch (1st-2nd c.) said "the Eucharist is the flesh of the Redeemer," while St. Irenaeus (3rd c.) stated that "we receive the bread as Jesus", and St. Cyprian (3rd c.) "Christ is our bread".[74]

Confession and other sacraments[edit]

While some Protestants, such as Lutherans, have retained the sacrament of Confession and Absolution,[75][76] critics say that a number of Protestants reject Jesus' authorizing the Apostles to "forgive sins" (Jn 20:23) and St. James admonition to "confess your sins to one another" (James 5:16) as they do have the sacrament of Confession.[77]

Also, "Peter taught that 'Baptism now saves you' (1 Pt 3:21) and thus is not a mere inciter of faith. The Bible speaks about 'anointing the sick with oil' (Jas 5:14-15), two kinds of laying of hands (Acts 8:17; 2 Tim 1:6), and marriage in the Lord (1 Cor 7:39)."[74]

The rejection of the seven sacraments, says Catholic critics, show that Protestantism does not accept the Incarnational principle: In Jesus, God united to his divine person a human nature, a material body and a soul. Thus, "God demonstrates at once that creation, including human nature, is not only good but is capable of being further elevated through the impenetration of the Divine life. This is the basis of the entire sacramental system, which uses outward (material) signs to transmit to us a share of God's life, from the initiation of the believer's journey in Baptism to its conclusion in Anointing of the Sick. It is the basis of the Church, a visible society which itself serves as a living connection between God and man, a sort of meta-sacrament for the transmission and embodiment of grace."[78]

Peter and the Popes[edit]

Protestants are criticized for not accepting Jesus' word to Simon whom he renamed Petros, meaning rock, and gave him the primacy of jurisdiction in his singular Church, despite the fact that many leading Protestant Bible scholars have accepted the passage's Petrine meaning:[79] "On this rock, I will build my Church and I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven" (Mt 16:18-19). He gave Petros or Peter, "the keys of the kingdom", which according to Scott Hahn, refers to the power of a prime minister of the King and chief teacher, based on the Old Testament. (Is 22:22). Also, Jesus told him alone to "feed my sheep" (Jn 21:15-17), while the Acts of the Apostles shows Peter leading the Church.[74]

Dave Armstrong presents "50 New Testament proofs" on the pre-eminence of Peter, saying that the "biblical Petrine data is quite strong, and is inescapably compelling".[80] He cites Peter as first in all lists of apostles, first to enter the empty tomb, to perform a miracle, to preach repentance, to recognize heresy, declare an anathema, etc.

The early Christians referred to Peter's Roman Church as "presiding" (Ignatius, 1st -2nd c.), "of superior origin" and standard of "true Faith" (Irenaeus, 2nd c.), "Chair of Peter", "the principal" (Cyprian, 2nd-3rd c.), and "the primacy" (Augustine, 4th-5th c.).[74]

Visible hierarchical church[edit]

Both Orthodox Christians and Catholics criticize Protestantism for their lack of belief in a visible, hierarchical Church[81] Scott Hahn said if St. Paul wanted to teach about an invisible Church, as the Protestant say the Church is, he would have called it Christ's soul. Instead, he chose the word "body" to refer to the Church in order to deliberately emphasize that the Church is visible like Jesus Christ.[27][13] The Church that Jesus built, say the critics, included apostles and sacraments (water, bread, etc.), which are visible signs.

Mary and the saints[edit]

Catholic critics say the Protestant lack the help that devotion to Mary and the saints provides and that Protestant opposition to them is unscriptural and does not follow early Christian practice. Scriptures, Catholics assert, refer to (1) "supplication, prayers, intercessions" as "good and acceptable" and also efficacious in bringing peace in 1 Tim 2, where scripture talks about Jesus as "one mediator", thus showing this singularity of Christ's mediation is compatible with Jesus' wanting subordinate, ministerial intercessors who are "in Him", as the Bible often says, showing the glorious greatness of his mediating powers,[82] (2) "prayer of all the saints" in heaven in Revelations (7:15;8:3-4), and (3) the blessing, "Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord" (Rev 14:13), a blessing from God that men have to imitate.[27][83] Etched in stone in early Christian pilgrimage sites are prayers to the saints for the dead such as "Peter and Paul, pray for Victor."[27][84] St. Augustine in 400 A.D. wrote, "Christians pay religious honor to the memory of the martyrs, both to excite us to imitate them and to obtain a share in their merits, and the assistance of their prayers." St. Jerome too in 406 A.D. said, "If Apostles and martyrs while still in the body can pray for others, when they ought still to be anxious for themselves, how much more must they do so when once they have won their crowns, overcome, and triumphed?"

Also critics allude to (1) Mary's prophecy after being filled with the Holy Spirit that "all generations shall call me blessed, (2) the biblical principle of imitation of Christ who followed the fourth commandment "Honor your father and your mother"; honor in Hebrew means to give glory, (3) the woman clothed with the sun who is introduced as the new and most venerable Ark of the Covenent in Revelations, and (4) the example of the early church Fathers, who called her the Mother of God, the New Eve, and a virgin who saved the human race (St. Irenaeus in 2nd c.). St. Cyril of Alexandria before A.D. 444, greeted her with: “Hail to thee Mary, Mother of God, to whom in towns and villages and in island were founded churches of true believers.” And a 3rd c. oldest preserved extant hymn Sub tuum praesidium runs: “Under your mercy we take refuge, O Mother of God. Do not reject our supplications in necessity, but deliver us from danger.".[85]

Purgatory[edit]

Protestantism is criticized for denying what the Roman Catholic Church sees as the biblical foundations of the doctrine of Purgatory. Certain Protestant denominations, such as Baptists, are criticized for overlooking the practice of praying for the dead among the early Christians.

Nevertheless, although denying the existence of purgatory as formulated in Roman Catholic doctrine, the Anglican and Methodist traditions along with Eastern Orthodoxy, affirm the existence of an intermediate state, Hades, and thus pray for the dead,[86][87] as do many Lutheran Churches, such as the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, which "remembers the faithful departed in the Prayers of the People every Sunday, including those who have recently died and those commemorated on the church calendar of saints".[88]

Critics say that "As shown in their tombstones, the early Christians followed the Bible: 'Pray for the dead that they may be loosed from sins' (2 Mc 12:46), for 'nothing unclean can enter heaven' (Rev 21:27). It does not make sense to pray for the dead if they only go, as a number of Protestants say, either to heaven (with faith in Christ) or to hell (without faith). Jesus spoke about forgiveness in the age to come (Mt 12:32) and St. Paul stated that those judged after death by God are 'saved but as through fire' (1 Cor 3:13-15)."[74][27]

Reason and faith[edit]

While the Catholic Church championed the harmony of faith and reason, since man's reason is a creation of God who is the Logos (Reason), Protestantism separated faith and reason and thus denying faith an access to the whole of reality through reason, according to Pope Benedict XVI:

- Dehellenization first emerges in connection with the postulates of the Reformation in the sixteenth century. Looking at the tradition of scholastic theology, the Reformers thought they were confronted with a faith system totally conditioned by philosophy, that is to say an articulation of the faith based on an alien system of thought. As a result, faith no longer appeared as a living historical Word but as one element of an overarching philosophical system. The principle of sola scriptura, on the other hand, sought faith in its pure, primordial form, as originally found in the biblical Word. Metaphysics appeared as a premise derived from another source, from which faith had to be liberated in order to become once more fully itself. When Kant stated that he needed to set thinking aside in order to make room for faith, he carried this programme forward with a radicalism that the Reformers could never have foreseen. He thus anchored faith exclusively in practical reason, denying it access to reality as a whole....

- The West has long been endangered by this aversion to the questions which underlie its rationality, and can only suffer great harm thereby. The courage to engage the whole breadth of reason, and not the denial of its grandeur - this is the programme with which a theology grounded in Biblical faith enters into the debates of our time.[89]

Historical, sociological and ecclesiological critique[edit]

A basic premise of the Catholic historical critique is Cardinal John Henry Newman's statement that "To be deep in history is to cease to be a Protestant." Catholic historians believe that a detailed and honest study of the history of Christianity shows that the early church does not describe Protestant teachings and practices and mirrors the teachings and practices of the Catholic Church, and that this study can show the flawed roots of the Protestant Reformation.

Early church practices and beliefs[edit]

According to Robert Sugenis, in contrast with Protestantism, "the early Church believed in the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist, confession of sins to a priest, baptismal regeneration, salvation by faith and good works done through grace, that one could reject God's grace and forfeit salvation, that the bishop of Rome is the head of the Church, that Mary is the Mother of God and was perpetually a virgin, that intercessory prayer can be made to the saints in heaven, that purgatory is a state of temporary purification which some Christians undergo before entering heaven."[90]

Founders[edit]

Protestantism per se, critics argue, was not present in the beginning of Christianity, since the founders of Protestantism lived in the 16th Century. The reformers did not receive any legitimate mission from God, and did not show any signs that they did receive this mission,[91] unlike St. Peter who performed several miracles in the Acts of the Apostles and died a martyr's death,[92] and the Catholic Church with its many documented miracles in the saints, the Eucharist, relics, Marian apparitions, etc.

Another criticism lies in the moral quality of the founders of Protestantism. Luther was said to be anti-semitic, misogynist and cruel towards the poor.[93][94] His fellow reformer John Calvin described Luther as "craving for victory, using haughty and abusive language, delusional, insolently furious, and careless about propriety of expression and historical context."[95] He is accused of egocentrism or metaphysical egoism, due to his doctrine expressed in his statement that "I do not admit, that my doctrine can be judged by anyone, even by the angels. He who does not receive my doctrine cannot be saved."[96] Henry VIII, the founder of Anglicanism, was married six times and beheaded two of his spouses. John Calvin "never endorsed private or lay interpretation of the Bible." He claimed authority as a successor to the prophets and apostles, punishing those who did not share his interpretation of Scripture.[97] He took part in 58 death sentences, including torture and burning at the stake, and the exile of 76 people.[98]

Doctrinal contradictions and disunity[edit]

Protestant self-criticism stresses the fragmentation of the Protestant groups.[99] The ecumenical movement, which some trace to the 1910 World Missionary Conference, owes its genesis to a realization of a "scandal" of disunity among the Christian groups.[100]

The disunity is not in accord, say these critics both Protestant and Catholic, with the Bible's teaching on "one faith, one baptism", "one body" and being "united in the same mind and same judgement", (1 Cor 1:10) with the distinction of churches in the New Testament based on geography but not in doctrine.

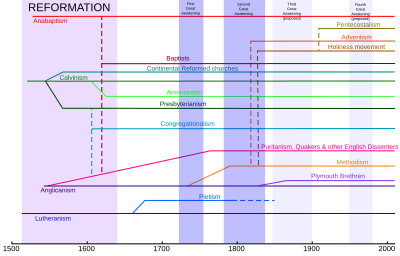

According to Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, there were 45,000 Christian denominations globally in 2015, while there were only 500 in 1800. The numbers are expected to grow to 55,000 by 2025. Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary estimates that a new Christian denomination is formed every 10.5 hours, or 2.3 denominations a day.[101]"approximately 45,000" from the Center for the Study of Global Christianity at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary.[102]

"Their views on the Trinity, on gays, etc. contradict each other. Since truth (e.g. Jesus is God) cannot be falsehood at the same time, real falsehoods are sadly being taught among these groups," says a Catholic theologian.[74] Also, as per Francis Beckwith, former President of the Evangelical Theological Society and a revert to Catholicism, Protestantism makes "schism as proper and unity as unnatural", promotes the subordination of Church and theology to the individual ego and prefers self-will over evidence.[103]

Non-universal autonomous denominations[edit]

While Protestantism has spread throughout the world, one Protestant self-critique points to the paucity or limited quantity of membership in individual Protestant denominations relative to the world population. Before he became Catholic, this was expressed by Peter Kreeft thus: "Why do we Calvinists have the whole truth and no one else? We're so few. How could God leave the rest of the world in error? Especially the rest of the Christian churches?"[104] The large autonomous denominations with their specific organizational leadership, truth claims, and group name, such as Southern Baptists, United Methodist Church, Church of England and Church of Sweden tend to have majority of their membership concentrated in one geographical area. This state of affairs, according to critics, is not in accord with the universal scope and mission that Jesus Christ gave to his Church.

Black legend against Catholics[edit]

For Protestant historian Pierre Chanu, and for philosopher Miguel Unamuno,[105] Protestants (and for Catholic scholar Ignacio Barreiro, Protestant ideology itself)[106] brought about the black legend, or false propaganda, against Catholics that have been spread in the United States and the rest of the Anglo-saxon world, and from there to the rest of the world. The black legend, or leyenda negra, was started by Protestant countries of Holland and Britain when Catholic Spain emerged as the major power after the wars of religion.

According to Rodney Stark, a non-Catholic scholar of Protestant Baylor University and who was a long-time agnostic, these Protestant countries "fostered intense propaganda campaigns that depicted the Spanish as bloodthirsty and fanatical barbarians." The spread of the black legends, bolstered by other forces such as the Enlightenment, led to many "notorious falsehoods" about the Catholic Church that have become common culture, he said. Reporting the prevailing view among leading scholars and specialists, Stark in his book Bearing False Witness: Debunking Centuries of Anti-Catholic History states that black legends include exaggerations and lies regarding the Inquisition, the Crusades, the Dark Ages, slavery and what he calls "Protestant Modernity". Modern capitalism with its wealth generation, according to the scholars, was not Protestant inspired, but "a Catholic invention", because of the historically verified existence of pre-Reformation Catholic capitalist communities in the 15th century. Thus, according to one of the greatest modern historians, Fernand Braudel, Max Weber's Protestant work ethic is "a tenuous theory" not accepted by "all historians", and "is clearly false."[107]

Contraception and the sexual revolution[edit]

Influential evangelical leader, Dr. Albert Mohler, the president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, said that the acceptance of a separation of sex and babies in contraception, pushed by "moral revolutionaries", led to the sexual revolution.[108] Starting in 1930, most modern Protestant denominations now favor contraception in contrast to the historical fact that before 1930 all Christian Churches without exception condemned contraception in the strongest terms.

For the critics, the shift in Protestant teaching is a result of lack of authority and fidelity to the God and Church tradition, a lack of "courage and integrity to teach this most unpopular truth".[13] Contraception is a caving in to immorality that, according to Pope Paul VI in 1968, "could open wide the way for marital infidelity and a general lowering of moral standards.... forget the reverence due to a woman, and ... reduce her to being a mere instrument for the satisfaction of [man's] own desires....public authorities...may even impose [contraceptive] use on everyone"[109] Social science research has demonstrated the correlation of contraception with the decadent sexual revolution, marriage decline, increase in teenage sex, adultery, illegitimacy, divorce and homosexuality, widespread porn, abortion, and government contraceptive impositions, according to critics. Thus, they say, science has proven that this "prophecy" has taken place, and Catholic teaching is the God-given truth.[110][111]

Scott Hahn said that the teaching against contraception in the history of the Church up to 1930 is based on a Biblical view of marriage as a sacred covenant, that creates family and kinship ties.[13] Tim Staples said the teaching of the Bible against the sin of Onan shows that those Protestants who accept the use of contraception are in error.

Hyperplural, permissive, state-controlled consumerist society[edit]

Notre Dame historian Brad Gregory in his multi-awarded The Unintended Reformation: How a Religious Revolution Secularized Society, published by Harvard University Press, argues that many ills of the secularized world, which he calls "Kingdom of Whatever", were unintended but essential consequences of the reformation. The contemporary world's hyperpluralism, relativism, lack of philosophical consensus on the most important things in life or what he calls "Life Questions" (such as the person one should become), and its individualist, egocentric subjectivism ('to think and do and live' as one may please, to 'exercise their wills as they will – the summum bonum') can be historically traced to sola scriptura, granting exclusive authority to the bible, which can be interpreted whichever way by anyone. Through the Reformation emerged "the new and compounding problem of how to know what true Christianity was. 'Scripture alone' was not a solution to this new problem, but its cause."

The modern secular state's control over morality and religion as shown for example in state imposition of the right to abortion and homosexual union is traced to the Reformation split between politics and morality (with theology), which were all united in pre-Reformation Europe. Luther's doctrine of the two-kingdoms "implicitly theorized the control of human bodies and thus human beings by secular authorities ... power [was] exercised by secular rulers alone." After the Reformation, Gregory says, "secular rulers were the sole stewards of the public sphere within which alone the flesh-and-blood social relationships of Christian life unfolded." With the transition from virtue ethics to an ethics of rights, Christianity "was radically redefined as a private and highly circumscribed matter of individual preference". With this, we now have "millions of divorces which, for decades, have exacted vast human costs. All this, too, is the product of individuals exercising their legally protected liberty, guided by the dominate ethos of a therapeutic society based on feelings."

He also says the Protestant Reformation "ended more than a thousand years of efforts in the Latin West to create a unified moral community through Christianity." Faith-alone doctrine without need of human cooperation in salvation, and "the bitter disagreements among early modern Christians about the objective morality of the good" led to "the absence of any substantive common good," subjectively constructed morality, and the "inexorable trend toward increasing permissiveness". Since one's personal happiness was most important, what emerged was "an all-persuasive consumerism wedded to a staunch faith in market capitalism". The state's main role was to protect and advance this. The fact that the Church voice on avarice as sin was restricted to the private sphere has "provided increasingly unencumbered, self-constructing selves with a never ending array of stuff to fuel constantly reinforced acquisitiveness." Because Christianity was removed from the political and economic sphere, education too was secularized, not intellectually open to God and to natural moral law: "an ideological imperialism masquerading as an intellectual inevitability." He says the contemporary academy is a "buyers'-market hyperpluralism" whose "aim is not the pursuit of truth...with respect to any of the Life Questions, but rather indoctrination in the conviction that there are no definitive answers." And “specialized academic research tends to discourage critical inquiry about the character and presumptive neutrality of intellectual assumptions that are routinely taken for granted. One cannot be aware of problems one does not see."[112]

No comments:

Post a Comment